Earliest source: William Cranch Bond. "Description of the Observatory at Cambridge." Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences vol. 4. Metcalf and Company, 1849.academybond

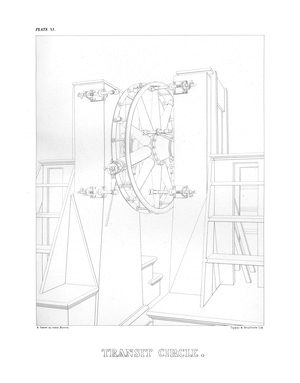

This is a drawing of the Observatory's best transit circle. It's a telescope, but it's mounted such that it can only rotate on a single axis. Most of these instruments were oriented along the meridian, and in that case were also called meridian circles. Meridian circles are used to precisely measure the timing of stars as they transit the meridian.

The Observatory possessed at least two meridian circles, as well as two "prime vertical" telescopes, which are transit circles oriented perpendicular to the meridian, rater than parallel to it.

This transit circle was mounted on one of the permanent piers built for that purpose, shown in other diagrams. It consists of a 4.5 inch refractor, made by Merz (same as the Great Rerfractor). This is mounted on a wheel four feet in diameter, consisting of a cast metal circle on each side, preciesly marked off around the perimeter in five minute increments. Eight "microscopes" mounted on the pier are used to read these markings, and a micrometer (in the eyepiece? or in the microscopes?) is used to accurately determine the direction of the telescope down to one arc-second, and estimate down to one fifth arc-second.

As early as 1844, the Observatory experimented with comparing remote transit times using telegraph connections to other observatories to determine longitudinal difference between locations. Telegraphs (which we now call the Victorian Internet) were a critical part of astronomical studies of that era. The Observatory had at least four permanent telegraph lines by 1887, and six by 1898.

Fine's Home

Fine's Home